Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1770-1831) | Issue 159

Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Brief Lives

Warren Ward looks at the history of a man who looked at the history of the world.

G. W. F. Hegel was the leading figure in the nineteenth century movement known as ‘German Idealism’. These idealists had responded to Immanuel Kant’s work in a manner that Kant would never have approved. Kant believed that although the external world existed beyond our experience of it, we could never know it as it is ‘in itself’ – we could only ever know the world as shaped by our minds to give us our experiences of it. Hegel built on this conclusion to argue that the only thing we can therefore be sure of existing is the consciousness with which we experience the world. So he rephrased the world in terms of consciousness – which is what ‘idealism’ means.

Paradoxically, the most significant legacy of Hegel’s work has been his influence on Marx, a dyed-in-the-wool materialist. That was because Marx was captivated by Hegel’s use of Heraclitus’s idea of ‘dialectic’ to explain how society has unfolded throughout history – of which more later.

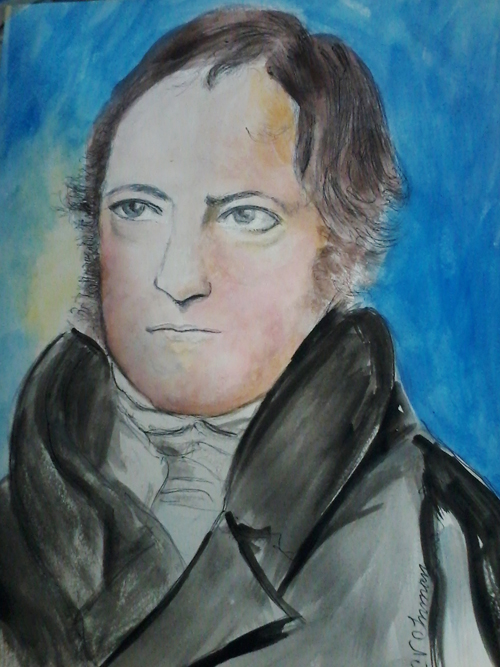

Young Hegel by Clint Inman

Hegel’s Early Stages

Hegel was born at a highly significant time in history, just as the thousand-year-old Holy Roman Empire was coming to an end. And, within twenty years of Hegel’s birth, the barricades and muskets of French revolutionaries would sweep aside a millennium of medieval feudalism to usher in new foundations of democratic republicanism that endure to this day. These dramatic events would leave a lasting impression on the young Hegel, and greatly influence his ideas.

Hegel started his schooling early. His parents sent him to a German school in his home town of Stuttgart when he was three years old, and then to a Latin school when he turned five. When Hegel was eleven, his much-loved mother died of ‘bilious fever’. Immediately after his mother’s death, Hegel developed a speech impediment that stayed with him for the rest of his life. At fourteen, showing much academic promise, he attended Stuttgart’s Gymnasium Illustre, where he was schooled in the classics, ancient and modern languages, physics, and mathematics.

When he turned eighteen, Hegel’s father enrolled him in the Tübingen seminary, hoping he would follow in the footsteps of uncles who had respectable positions as pastors. But Hegel found theology unbearably tedious. He was more interested in philosophy, and at the seminary he made two friends who shared this enthusiasm, Friedrich Schelling and Friedrich Hölderlin. Schelling would become another leading light in the German Idealist movement. His star would shine earlier, but in the end Hegel’s would shine more brightly. Hölderlin would become one of Germany’s most revered Romantic poets, and a celebrated leader of the Sturm und Drang literary movement.

Hegel was only nineteen when he and his comrades heard the sensational news of the French Revolution: that France’s ruling aristocracy had, almost overnight, fallen by the will of the people. They were exhilarated that the ideas of their philosophical heroes Kant, Voltaire, and Rousseau were inspiring the French nation into a radical new society, and fervently hoped it would spread eastwards (it didn’t).

After completing his five-year course at Tübingen, Hegel eschewed opportunities to work as a pastor, and instead took up a position as a tutor for one of Berne’s wealthiest families. Hegel’s new employer boasted an extensive library, and Hegel worked his way through its collection of classic and contemporary texts. It was here that he came across Edward Gibbon’s History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire (1776). Its detailed and comprehensive account of the fate of Europe’s greatest empire would become a major source of inspiration for his work.

In January 1801 Hegel received an invitation from Schelling to join him in Jena. Although Schelling’s invitation didn’t include the sort of paid academic position Hegel was looking for, it did bring him into the embrace of a forward-looking academic community brimming with new ideas. Overseen by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Jena’s university was becoming renowned as a centre of post-Kantian idealist philosophy, Weimar Classicism, and German Romantic literature. Jena was also a place of romance for Hegel, too. At the age of thirty-seven he started an affair with his landlady, Johanna Burkhardt, who soon fell pregnant with their son, Ludwig.

Aware that he would soon have another mouth to feed, Hegel worked away every night at finishing his first major work, Die Phänomenologie des Geistes (The Phenomenology of Spirit). It proposed a new theory, now called dialectical idealism, which contended that the evolution of society throughout history is shaped by gigantic, invisible, often contradictory forces.

As if to underline this theory, on 13th October 1806, Napoleon’s armies entered Jena – just as Hegel was putting the finishing touches to his manuscript. With Jena in ruins and no work in sight, Hegel moved to Bamberg to take up employment as a newspaper editor. He left baby Ludwig and Johanna behind, promising he would return to marry her as soon as he was able.

In April 1807, Hegel published The Phenomenology of Spirit in Bamberg. This monumental work had arisen out of several sources of inspiration: Hegel’s study of history, his observations of the French Revolution, and his reading of Kant’s conclusion that the real world could never be truly known. As I said, like other German idealists, Hegel believed that the only thing we can be sure of is the consciousness with which we experience the world. Hegel integrated this idea into his historical thinking, to say that history is the process of consciousness coming to know itself. In the Phenomenology, he traced how, over the ages, societies had become more sophisticated, human culture inching closer to what Hegel saw as the ultimate state of self-knowledge. He predicted that this process would eventually culminate in human society becoming perfectly self-aware – a state he called Absolute Spirit.

When it was first published, The Phenomenology of Spirit stimulated only a modest response in philosophical circles and the wider reading public. This was no doubt partly due to its turgid and difficult-to-read style – a style that would characterise all of Hegel’s work. In the months following its publication, however, as readers untangled and deciphered the awkward prose and better grasped the ground-breaking ideas, appreciation of the work grew, as did Hegel’s reputation and standing in the academic and wider communities. With this increasing fame, Hegel soon forgot about Johanna and Ludwig languishing in Jena, and began to look for a wife more in keeping with his newfound status.

In 1808, Hegel was offered a prestigious position in Nuremberg as rector of its leading high school. It was here that Hegel met Marie von Tucher, the nineteen-year-old daughter of a respected Nuremberg patrician. Although Johanna tried to disrupt their wedding preparations, Hegel proceeded, unperturbed, with his plans to marry into the higher echelons of society. He was now making some social progress of his own.

In the years after Hegel’s wedding he had a burst of productivity, publishing his second highly acclaimed work, The Science of Logic, in three volumes from 1812 to 1816. This work helped him achieve his long-awaited goal of appointment to a professorship of philosophy. And after two years at the University of Heidelberg, he was offered an even more prestigious position at the University of Berlin.

The Culmination of Hegel

When Hegel arrived in Berlin in 1818, it was the capital of the biggest German state, Prussia; the fourth largest city in Europe; and a thriving centre for music and the arts. Berlin society welcomed the famed philosopher and his elegant young wife with open arms. At forty-eight, he had reached a peak in his career. The Science of Logic had further expounded on his central idea in The Phenomenology of Spirit, to say that reality is not only shaped by the mind, it is mind. It cemented his reputation as one of Germany’s boldest thinkers since Kant. Hegel’s lectures were well-attended, and became the talk of Berlin; his stutter and obscure manner of speech, ridiculed by some in the past, was now seen as part of the larger-than-life philosopher’s charm and intrigue.

On hearing news of Johanna’s death, Hegel rescued his illegitimate son from an orphanage to take him into his family along with the two sons that Marie had borne him. Ludwig, however, did not fit into Hegel’s wealthy bourgeois household, and Hegel felt torn between his duties to his wife and her sons (who weren’t that fond of the new addition to their family) and his obligations to Ludwig and his late mother. Indeed, Hegel’s personal life was now beset by dialectical tensions akin to those he wrote about in his philosophy.

In 1821 Hegel published his third major work, The Philosophy of Right, which laid out his thoughts on political philosophy. He argued that law was the cornerstone of the modern state. He was disappointed that this book was interpreted by many as demonstrating sympathies with the right-wing Prussian monarchy.

Meanwhile, his life at home was becoming increasingly disrupted by conflict with Ludwig, whom he eventually ejected out of the house and disowned after he found him stealing money from the family kitty. Ludwig enlisted with a mercenary army in Amsterdam, and sailed to Java to fight in the colonial wars.

In 1831, along with everyone else in Prussia, Hegel found himself alarmed by reports of a cholera pandemic tracking across Asia towards Europe. When the first case of cholera hit Prussia that August, all slaughterhouses, schools, and other public buildings were closed, and royal orders were given for all coins and mail to be fumigated with smoke or sulphur. As more cases were reported, the King issued a decree that all affected houses in Berlin were to be quarantined. Hegel and his family packed their belongings and moved to the safety of Kreuzberg, just outside Berlin, where a family friend allowed them to rent out the top floor of their home.

The epidemic raged for months in Berlin as Hegel and his family waited it out in Kreuzberg. Although Hegel remained nervous about the cholera spreading to their new location, these months were a time of quiet and precious respite for the family. Marie referred to their temporary living space as die Schlösschen – their little palace – and during these weeks Hegel whiled away leisurely days in the house’s back garden playing chess with his sons, reading the newspaper, and, as ever, writing philosophy.

After officials declared the epidemic was over, the family moved back to their home in Berlin. But the ageing philosopher didn’t feel secure, despite assurances from authorities that the danger had passed. He complained to Marie that the dirty Berlin air made him feel “like a fish that had been taken out of a fresh spring and thrown into a sewer.”

As it turned out, the philosopher’s gloomy premonitions were not misplaced. At 11 a.m. on Sunday, 12 November 1831, only a few days after he had arrived back in Berlin, Hegel was struck with a severe attack of abdominal colic. The next day his condition deteriorated: he was no longer able to urinate, and started wildly hiccoughing. Later that afternoon, his family found him motionless and not breathing, his face a stony grey. A doctor was called, and duly pronounced the death of the city’s latest cholera victim. Hegel would never receive the news that a few months earlier his twenty-four-year-old illegitimate son Ludwig had been found dead on a battlefield in Batavia.

Post-Hegelian Conclusions

At the height of his fame, Hegel was seen as the thinker of his age, spokesman par excellence for post-revolutionary, post-Napoleonic Europe. After his death, Hegel’s students hurried to transcribe his lectures, believing he was one of the few men who grasped the changes sweeping Europe, as the church and aristocracy gave way to Napoleon’s vision of a more egalitarian, humanistic society.

Even after his death, the ebb and flow of Hegel’s influence resembled the moving tides of history he described in his philosophy, as his followers split into two opposing camps: the Left Hegelians, who believed further revolutionary changes were needed, and the Right Hegelians, who ardently defended the Prussian monarchist state.

One of the more radical young Left Hegelians was a young man called Karl Marx (1818-83). Marx transformed the next century’s political landscape with his ideas on how Europe should respond to the challenges and inequities posed by the rise of capitalism and mass industrialization. Today we refer to these ideas as ‘Marxism’ or ‘Communism’, but Marx called his theory ‘ dialectical materialism’ in acknowledgement of the fact that it was directly inspired by Hegel’s dialectical idealism.

Although Hegel’s rather mystical philosophy is out of keeping with the scientific, materialistic worldview that dominates today, his interest in understanding history has had a persisting influence, not just in continental philosophy, but more broadly in academic and popular thought.

© Warren Ward 2023

Warren Ward is Associate Professor in Psychiatry at the University of Queensland. He is the author of Lovers of Philosophy: How the Intimate Lives of Seven Philosophers Shaped Modern Thought (Ockham Publishing: 2022).