How to Have a Good Life | Issue 160

Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Articles

Meena Danishmal asks if Seneca’s account of the good life is really practical.

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the adjective ‘stoical’ means “resembling a Stoic in austerity, indifference, fortitude, repression of feeling and the like”. This gives us some idea of what it is like to be a Stoic. Indeed, the key teaching, arguably the fundamental point, of Stoicism, is that we should focus on controlling the things that are under our control, such as our thoughts, emotions, and actions, whilst accepting those things we cannot control, such as most things that are happening in the world. How did they get there?

To consider this question let’s look at the ideas of the Roman philosopher and statesman Lucius Annaeus Seneca the Younger (4 BCE-65 CE). As a top advisor to the paranoid and murderous Emperor Nero, he probably found Stoicism a particularly practical guide to life.

As a Stoic, Seneca believed the soul (Latin: anima or animus) to be a finer form of matter than the body; but matter it is. It was also described as a spark of the fire which had consumed the original matter. With such an understanding of the soul, where does the soul reside within the body? Stoics provided a rather simple answer: everywhere. The soul was considered to be a vital force that animates the whole body. The soul was also the source of reason, virtue, and moral character, which is what Stoic philosophy is built upon, as the rational soul guides individuals towards living in accordance with nature.

For us to understand this concept further, it’s vital to grasp the Stoic conception of reality. Stoics see the universe as interconnected and interwoven, and this unified cosmos as governed by rational principles. Within this holistic perspective, the soul is seen as part of the divine rational order of the universe. This understanding forms the basis of Stoic ethics, which emphasises the importance of cultivating reason and virtue in all aspects of life. This encouragement to align thoughts, actions, and desires with principles of reason, is a way for the soul to flourish.

Seneca believes it’s vital to make room for leisure. However, a life of pure leisure is considered meaningless. He is also against making a show of everything. Those who do so are described as being ‘idly preoccupied’, and squandering their lives on pointless endeavours. He also criticises people who obsess about their appearance, and asserts that they are not truly at leisure. We are squandering time, which is the most valuable resource of all, by concentrating on how we appear. You may have heard this quote before: “It is not that we have a short time to live, but that we waste a lot of it.” Seneca wrote this in order to urge us to examine life honestly. Our lives feel short because they’re filled with business and stress. In essence, many of us are wasting our potential, living what could be described as a life of ‘simple existence’, simply responding to the random events of life. Seneca, though, describes genuine living as being in charge of oneself and hence either meaningfully enjoying yourself or striving towards objectives that are significant to you. To showcase this contrast he uses the analogy of a boat in a storm:

“For what if you should think that a man has had a long voyage who had been caught up by fierce storm as soon as he left harbour, and, swept hither and thither by a succession of winds that rages from different quarters, had been driven in a circle around the same course? Not much voyaging did he have, but much tossing about.”

(On the Shortness of Life, c.49 CE)

Perhaps the most important lesson of his essay On the Shortness of Life (De Brevitate Vitae) is that we need to value our time and avoid wasting it. Yet it is not just a matter of understanding this idea, but of translating it into day-to-day life. Also remember that you could die at any point. (Seneca himself committed suicide on Nero’s orders, when suspected of involvement in a plot.)

In On the Shortness of Life, Seneca provides some valuable lessons, not only regarding oneself but also regarding the nature of relationships; for instance, “You’ve no right to expect anyone to pay you back for those services; when you offered them, it was a wish to be with someone else but an inability to be with yourself.” I remember the first time I came across this quote it rattled me – in a positive manner: it’s a reminder that true acts of service should be performed without an expectation latched onto them, and it highlights the importance of selflessness and genuine compassion, to engage in acts of service with a sincere desire to contribute to the well-being of others. It also indirectly encourages one to cultivate a healthy relationship with oneself. By doing so, fulfilment can be discovered within our actions whilst also maintaining a balanced approach to our personal growth within society.

If after this article you still wish to read On The Shortness of Life, then do be prepared for some brute facts. It’s not for the faint-hearted.

Seneca the Younger by Stephen Lahey

Critiquing Seneca’s Stoicism

Although Seneca left behind a wealth of wisdom in his writings, it is nevertheless essential to critically examine his account, since some of his teachings may be impractical for those seeking a well-rounded approach to life. For instance, he frequently expresses an idealistic view of human nature and expectation of human conduct, but the stringent dedication to reason and virtue the Stoics promote might be difficult for most people to maintain amid the complications of everyday life. And while Seneca’s emphasis on controlling emotions and impulses is admirable in abstract theory, this ignores the complex reality of human psychology. In practice, it can be extremely difficult to achieve such a level of self-control in every situation. Humans are complex beings with a wide range of emotions, and expecting most people to suppress their natural reactions entirely is unrealistic. Although striving to manage emotions and desires can be valuable, Seneca’s account perhaps neglects the importance of healthy emotional expression and genuine human experiences. Contingent biological factors have almost been neglected in Seneca’s account, too. For instance, women suffering from PCOS tend to have larger mood swings due to the condition causing a hormonal imbalance, whereby their control of their emotions can be severely limited.

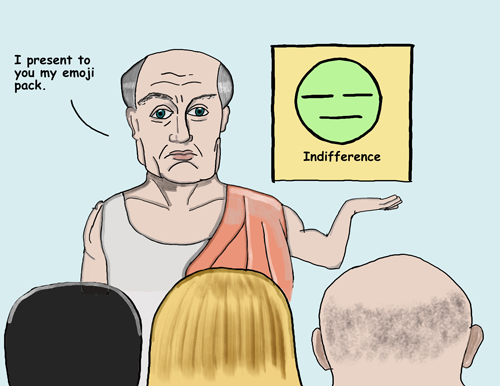

As a Stoic, Seneca places great importance on detachment from circumstances and the cultivation of indifference towards events beyond our control. Yet while it is undoubtedly beneficial to maintain emotional resilience, Seneca’s account often leans towards a radical detachment which may dissuade followers from actively engaging in society and working for social change. At the logical extreme, Stoic indifference may result in a complete withdrawal from relationships and societal responsibilities, to the detriment of all. Empathy and social connections, are after all, essential components of a good life. A more realistic outlook on life should strike a balance between acknowledging the limits of our affecting the world and actively interacting with it to make a positive difference.

Stoicism emphasises the value of individual responsibility and inner fortitude; but it is also crucial to recognise the outside forces that affect a person’s situation. So Seneca’s universal recommendations are less appropriate to the intricacies of real life in as much as they don’t take contextual considerations into account. The distinctiveness of each person’s situation and the variety of difficulties we face are frequently disregarded in his teachings. But people come from various origins, experience various socioeconomic situations, and face particular challenges. Access to resources, opportunities, and support networks is not universally equal. Instead of proposing a one-size-fits-all solution, then, a practical outlook on life should take these factors into account, and adjust accordingly.

Seneca’s account might also minimise the value of emotional intelligence and the value of the capacity to comprehend and manage our emotions in a healthy way. Our emotions are an essential part of the human experience, and provide important information about our needs, wants, and values. Emotional numbness, and a separation from our true selves, can result from suppressing or ignoring our feelings. Practically speaking, this can also impede personal development, and prevent people from being self-aware and emotionally resilient. People benefit more from developing emotional intelligence, empathy, and compassion, than from trying to conceal or remove their emotions because emotional intelligence, empathy, and compassion can lead to general well-being and more satisfying relationships. So recognising the complexity of emotions and learning to harness their potential for personal growth would be a better approach.

Seneca also frequently establishes lofty ideals for moral behaviour. Although striving for noble ideals is laudable, the Stoic concentration on obtaining self-control and equanimity can put undue pressure on people and cause feelings of inadequacy. Those who are unable to constantly uphold these elevated goals may feel a sense of failure, which could lead to anguish and disappointment. A more realistic outlook on life would recognise that people are fallible beings who suffer flaws and make mistakes. So instead of aiming for an unreachable level of virtue, people should concentrate on improving themselves constantly, on learning from their mistakes, and on developing a sense of personal integrity. A more realistic and longer-lasting path to self-fulfilment can be found by putting the emphasis on growth and progress rather than on achieving perfection.

Lastly, the Stoic stress on independence and self-sufficiency ignores the essential interconnectedness between people. Stoicism frequently downplays the value of interpersonal relationships and the contribution that a supportive community makes to living a happy life. Yet since humans are naturally social creatures, maintaining positive relationships and asking for help from others are essential to happiness. Following Seneca’s account might deter people from making and fostering deep connections.

Seneca the Emoji Developer

© Addie Luo 2024

Understanding the importance of interpersonal connections, empathy, and social support is crucial to taking a practical approach to life. Building and sustaining positive relationships with others can promote self-development, resilience, and overall happiness. A more contented and balanced life can be attained by actively participating in our communities than by striving for self-sufficient individualism.

Troubled Reflections

While Seneca in On the Shortness of Life provides some insightful analyses, it is vital to assess his essay’s applicability in everyday situations. Seneca’s practical recommendations are impracticable due to his Stoicism’s idealistic quality, stress on objectivity, disdain for unique circumstances, poor recognition of emotional complexity, exaggerated expectations of virtue, and omission of human interdependence. A more realistic outlook on life would require striking a balance between reason and emotional intelligence, considering the unique circumstances of each person, and putting an emphasis on one’s own development, self-compassion, and meaningful relationships with others.

© Meena Danishmal 2024

Meena Danishmal is a political philosophy writer as well as an undergraduate studying Politics, Philosophy and Economics at Royal Holloway University of London.

• To read about a Stoic philosopher from the other end of the Roman social spectrum, the former slave Epictetus, see Massimo Pigliucci’s column in this issue.

Advertisement