Are 3,000-year-old carvings from Italy a star map? Researchers can’t agree.

A roughly 3,000-year-old stone disk covered with enigmatic markings is actually an ancient celestial map marking the brightest stars in the night sky, researchers claim.

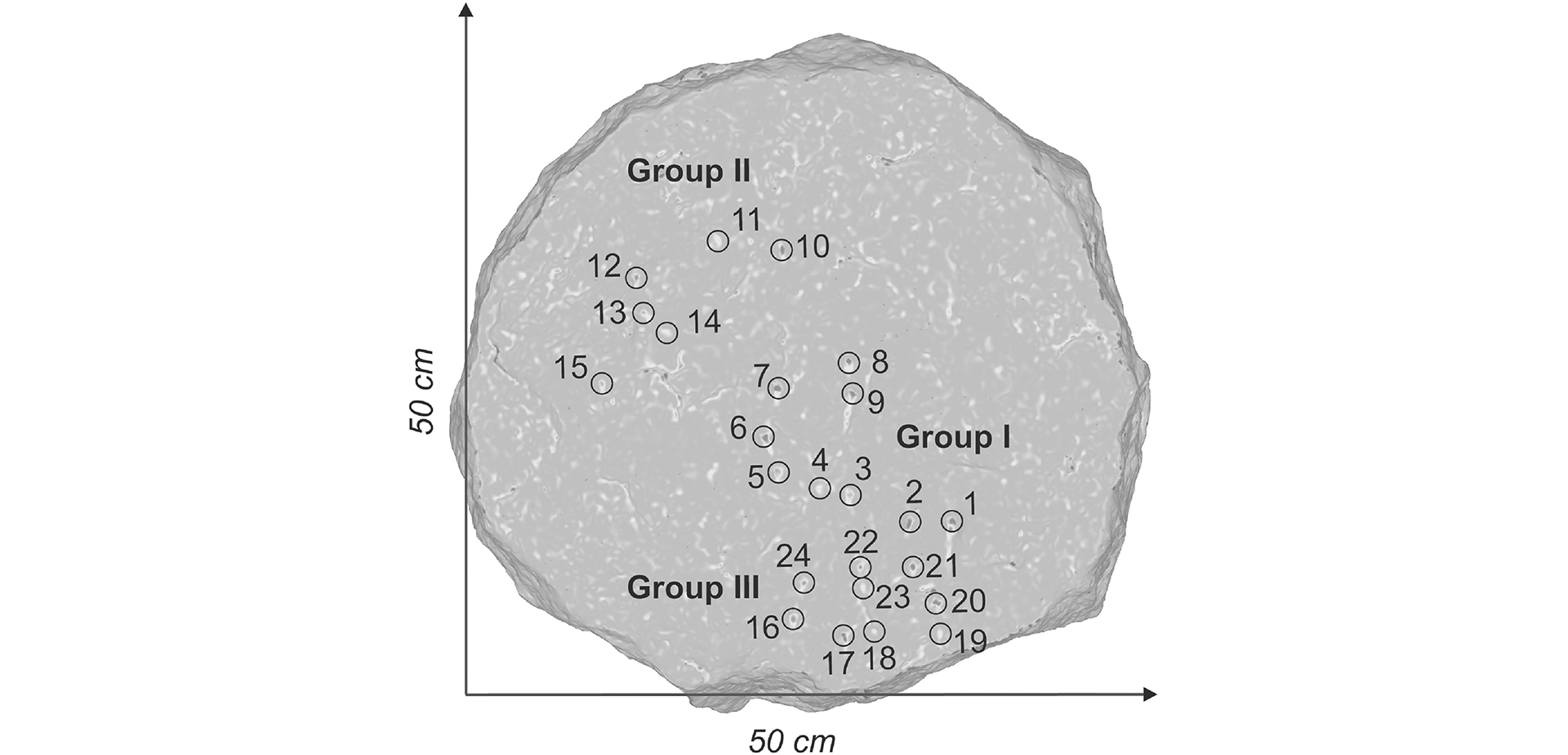

The tire-size stone, which was discovered near an ancient hill fort in northeastern Italy a few years ago, features 29 carved markings on its front and back that may represent the brightest stars in the night sky, researchers posit in a new study, published on Nov. 22 in the journal Astronomical Notes.

However, astronomer Ed Krupp, the director of the Griffith Observatory in Los Angeles, who was not involved in the stone’s discovery, told Live Science he thinks any relationship between the carved markings on the stone and the brightest stars may be accidental.

“Could these marks represent asterisms? They could,” he said. But “does the paper argue a persuasive case? No, it doesn’t.”

Krupp is the author of a study examining previous efforts to identify asterisms in rock art, which will be published in a few months. He is also the author of “Echoes of the Ancient Skies: The Astronomy of Lost Civilizations” (Dover, 2003).

Related: 2,000-year-old ‘celestial calendar’ discovered in ancient Chinese tomb

Ancient stones

The stone disk is one of two found near the entrance of a hill fort at Rupinpiccolo near Trieste — possibly in a cemetery, according to a 2022 study that announced its discovery. A similar pair has been found near Gradina in the Brijuni Islands off the Croatian coast, about 60 miles (100 kilometers) farther south.

The forts are dated to the region’s “protohistoric” period — the transition between the prehistoric and the historic periods — between 1800 and 400 B.C. But the authors of the latest study note the possibility that the stone disks may have been made later.

One of the Rupinpiccolo stones is blank, and the researchers suggest it may have represented the sun.

They also suggest that 28 of the marks carved on the front and back surface of the other stone disk correspond to prominent bright stars, particularly those in the constellations Scorpius and Orion, which would have been rising in the eastern sky just before the sun at that time — an occurrence known as “heliacal rising.”

Astronomer Paolo Molaro of the Astronomical Observatory of Trieste, the lead author of the latest study, told Live Science that the statistical precision, scale and orientation of the carved marks were evidence that they represented real stars in the sky.

He noted that the Greek poet Hesiod, writing in the eighth century B.C., had described using the heliacal risings of star patterns like Orion and the Pleiades to determine the time for planting crops.

“It is likely that this practice spread among the protohistoric communities much before that,” he said. “This suggests that the stone may have been some kind of calendar.”

Mystery star

The study does not explain the mysterious 29th mark carved on the surface of the stone disk near the supposed representation of the constellation Orion, and it corresponds to no known star. However there are some possibilities as to what it could represent.

Among the most intriguing is the idea that the 29th mark may depict a supernova that was visible when the disk was made but later faded from view; and it may be that a black hole or supernova remnant is still at that location today, Molaro said.

Little is known about the culture of the Castellieri, the Bronze Age people who built more than 100 hill forts in the ancient Istria region of the northeast Adriatic; and the precision of the star map is surprising, he said.

Related: 100,000-year-old story could explain why the Pleiades are called ‘Seven Sisters’

“In this case, the reconstruction is astronomically faithful,” he said. “The comparison must therefore be made with the [star] catalog of [Greek astronomer] Hipparchus in the second century B.C.”

Wishful thinking

Krupp, however, disagrees that the stone is a celestial calendar. “For me, the paper is over-argued, and the invocation of an imaginary supernova is indicative,” he said. “The statistical argument suggests something is there that doesn’t really seem to be there, and that can happen with such analyses.”

While many such objects might be attempts at star maps, such claims require clear evidence, he said.

“We need more than similar patterns,” he said. “We are pattern-seeking creatures, but we are not always rigorous in our efforts to determine whether the patterns we see are meaningful.”

Krupp noted that he was nonetheless impressed by the professional discipline and analyses in the previous study.

“I don’t have any quarrel with the authors’ serious intent,” he said. “I believe, however, the possibility of celestial representations in the chisel marks was just too tempting for them.”

He also said that there needs to be a clearer link between these ancient marks and the night sky to be fully convincing. “I don’t argue that prehistoric representations of asterisms have to be perfect; many known representations of star patterns are not,” he said.

“But most of the time, when there is no persuasive independent converging line of evidence, you have only wishful thinking,” Krupp said. “This is wishful thinking.”