Stoicism in History & Modern Life | Issue 157

Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Articles

Dermot M. Griffin reflects on the sources and relevance of this ancient wisdom.

Over the past twenty years there has been an increase in interest in Stoicism. Founded by Zeno of Citium around the third century BC, Stoicism is one of the many great schools of Hellenistic thought, and it is still relevant for several reasons. The root word for the school comes from the Greek stoa, referring to the porch that Zeno gave his lectures on in Athens marketplace. This is no accident: Zeno wanted his tenets to be useful for everyone. Stoicism is not a philosophy well suited to the college or the academy, since it does not emphasise abstract thinking or setting up hypothetical scenarios and models. Rather it is the ordinary person’s philosophy, the philosophy of traders, athletes, soldiers, and blue collar workers.For the Stoic, philosophy is pragmatic; it is meant to help the individual navigate through real world situations. The fact that the person in the street can apply the principles of this system to everyday life is one reason it is so appealing. The nature of Stoicism (and perhaps of all philosophy) is best described in the words of the Stoic Epictetus: “Philosophy does not promise to secure anything external for man… For as the material of the carpenter is wood, and that of statuary bronze, so the subject-matter of the art of living is each person’s own life” (Discourses 1:15). Paraphrasing something else Epictetus said, the lecture hall is a hospital, and all who enter it are in a state of pain (Discourses 3:8).

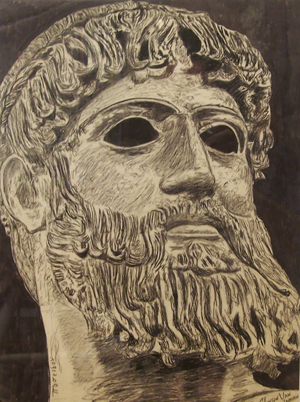

Zeus by Clint Inman

© Clinton Inman 2023 Facebook At Clinton.inman

The main idea behind Stoicism is that every human being has within them the drive for eudaimonia, or happiness, found through an authentic life guided by the use of our reason rather than our emotions. Stoics take the soft determinist position: we have free will but there are also certain things in life that are not in our power to control. If we focus on the things that are in our control (the prohairetic things), then we live a life guided by rationality. However if we decide to focus on things that are not in our control (or aprohairetic things), then the push towards harmful living is great, and we are thrown into living a life guided by irrationality. Bertrand Russell’s beautiful chapter on Stoicism in his History of Western Philosophy (1953) keeps the school’s ideas very straightforward: if one lets the uncontrollable alone and instead works on developing one’s character, then everything will work out. “Virtue,” says Russell here, “consists of a will that is in agreement with Nature.” The primary effect that Stoicism aims to bring about is apatheia, which means to not be disturbed by suffering. This does not mean that one will be free from the effects of suffering entirely, but rather that one is in a state of equanimity and knows what to do in situations that would otherwise harm one’s soul, or mind.

Because of its pragmatic approach, Stoicism flourished in the Roman Empire and played a big influence on Roman culture, also contributing to the development of Christianity. Contrary to what many people may think, Stoicism supports the idea of a supreme being. And unlike their Epicurean brethren, who believed in gods who were cold and indifferent to the affairs of men, the Stoics believed in a god that was very much active in the affairs of everyday life – the Logos, or divine reason. However, this is not to be confused with the biblical God; the Stoics offer no scriptures, and give our ability to reason as the greatest divine revelation of all.

Most people who read a Stoic book usually read the later Stoics, such as Marcus Aurelius (121-180 AD), Seneca (4 BC-65 AD), and Epictetus (50-135 AD). Let’s consider them in turn.

Marcus Aurelius

Marcus Aurelius was possibly the greatest emperor in the history of Rome apart from Augustus and Justinian. Born in Rome, he was the last of the Antonine Emperors, commonly called ‘The Five Good Emperors’. A just ruler and a brilliant military strategist, he had no desire to be a typical emperor. Rather, he sought to study philosophy and to live a quasi-ascetic lifestyle. Nevertheless, his career in both the military and his grooming for politics caused him to adopt a Stoic outlook. Interestingly, Aurelius never refers to himself as a ‘Stoic’ at all.

Aurelius’s magnum opus, Meditations, describes his thoughts on life. It’s a curious book. Written entirely in Koine (common) Greek, we can assume that the text was initially untitled, and also that he had no intention of it being published. This begs the mind-boggling question: why would a man write a book not to be published? Was this text truly for himself – a simple journal of his trips around the empire and his practice of daily living? Or did this book serve another purpose? Aurelius’s son Commodus (161-192 AD) came to the throne due to his father’s death after the Antonine Plague, one of the deadliest plagues in Rome’s history. Commodus was not at all a good ruler; the events that would lead up to the Third Century Crisis, and the tragedies that would start to weaken the western half of the Roman Empire, were largely put in motion by him. Could Marcus Aurelius have foreseen the hardships that his empire would go through if not led by a strong and wise leader, and therefore wrote Meditations as a guide for his son?

Aurelius wrote down principles that were to lead to a blissful life. His philosophy is not at all complicated. The Emperor bluntly tells us to “Put an end once and for all to this discussion of what a good man should be, and be one” (Meditations 10:16). Blunt again, he says “Soon you’ll be ashes or bones. A mere name at most – and even that is just a sound, an echo. The things we want in life are empty, stale, trivial” (Meditations 5:33). Judging by these statements, and countless others, Aurelius could almost be Schopenhauerian.

A classic idea attributed to Aurelius is the adage ‘ Memento mori’, commonly translated as ‘Remember you will die’ or ‘Remember your mortality’. This idea would do people of my generation some good to ponder. What would it be like to no longer exist? It’s bound to happen at some point. This forces us to think about how we’ve lived; and if we’re not living a life guided by reason, this may cause us to change our lifestyle.

Seneca the Younger

Lucius Annaeus Seneca, commonly known as Seneca the Younger to distinguish him from his father, was a great Roman governor, essayist and playwright. Born in what is now Spain and raised in Rome in a privileged family, Seneca studied rhetoric and philosophy from a young age. He became tutor to the feared emperor Nero, one of the worst emperors in Rome’s history, who eventually commanded him to commit suicide for allegedly being a member of the ‘Stoic Opposition’, an alleged coup d’etat by Stoic philosophers to overthrow him. He obeyed.

Seneca’s best known book is commonly called Letters from a Stoic, but the proper Latin title Epistulae Morales ad Lucilium means Moral Letters to Lucilius, the receiver of these being a governor of Sicily. One of the common themes is education. Seneca writes that “Life without learning is death” (Epistle 82); but he also says that “We do not learn for school, but for life” (Epistle 10), Seneca makes the point that education of any kind should be geared to making our lives better regardless of what one does with his or her life. Isn’t this extremely valid for today’s world? Kids often have little idea why they’re studying what they’re studying: to go to college or get a job? Those are the only two options; and sadly, many kids get lost on their way to finding their niche. This is perhaps why the humanities subjects are declining; their practical use is diminishing due to the anti-logical trend for relativism. Rather than read brilliant writers and study actual history, what becomes important is how each and every one of us ‘feels’ about a topic. Yet by Seneca’s logic, and the logic of Stoicism in general, if it doesn’t align with reason, the Logos, then it should be ruled out as illogical and thrown away.

Another one of Seneca’s works is On the Shortness of Life. This is the essay which tends to stand out to most people in Seneca’s corpus. In it he writes, “It is not that we have so little time but that we lose so much… The life we receive is not short but we make it so; we are not ill provided but use what we have wastefully.” Here Seneca makes it perfectly clear that human beings are autonomous, that is, we decide how to go about living our everyday lives; and if we decide to waste them then so be it; we’ve only made our suffering worse by doing so. Wastefulness is indeed embedded in the human soul, but we can make the conscious effort to work on taming this flaw by the application of Stoic thinking.

Epictetus

Epictetus is perhaps the most mysterious of the Stoic writers. He wrote nothing down and his Discourses and Handbook were both authored by his disciple Arrian.

Born a slave in what is now Turkey, he studied under the great Stoic thinker Musonius Rufus. Gaining his freedom shortly after the death of Nero, he fled to Rome, where he made a living teaching philosophy. Eventually banished from Rome by the emperor Domitian, he moved to Greece, where he spent the remainder of his life. His work had a huge influence upon Marcus Aurelius.

Epictetus’ thought is straight-forward in nature, and this is a good thing. His Handbook is perhaps the best starting point for people who want to get into Stoicism; it’s a short read in clear language. He tells us, “Man is not worried by real problems so much as by his imagined anxieties about real problems.” The word ‘anxiety’ – agonia – is almost existentialist in nature; the very idea of anxiety is of a concrete experience that one endures. Epictetus puts forward his remedy in epigrams such as “It’s not what happens to you, but how you react to it that matters” or “People are not disturbed by things, but by the views they take of them.” Epictetus is suggesting that if we change the way that we react to the stresses of life – if we change the way that we think – we become free. He says that our freedom is specifically gained by “disregarding things that lie beyond our control.” Or as his Discourses say, “On the occasion of every accident that befalls you, remember to turn to yourself and inquire what power you have for turning it to [good] use.”

The idea of changing our own mindsets as outlined by Epictetus and the rest of Stoic philosophy was known to influence Albert Ellis, the founder of Rational Emotive Behavioral Therapy, and Stoicism also influenced the development of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy. Such a system of thought can definitely benefit us in the hardships that we continue to face as a world.

© Dermot M. Griffin 2023

Dermot M. Griffin is a high school history teacher currently finishing a graduate in theology and philosophy.

• For more on Epictetus see Massimo Pigliucci’s column overleaf.