Ethics in Politics | Issue 153

Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Articles

Massimo Pigliucci trawls the history of politics to see how closely ethics fits it.

A good number of politicians talk about character, virtue, morality, and doing the right thing. But if you look at what they actually do rather than just listen to what they say, their behavior is often anything but virtuous. They lie, they cheat, and sometimes, they self-aggrandize, or start wars which bring misery to countless people.

Did you think I was talking about current politics in the US, the UK, or perhaps Russia? No, actually I was thinking of Renaissance Europe. It was a time when Popes, arguably the highest role models in Christendom (after Jesus himself, of course), sometimes donned armor and rode into battle – when they were not scheming to augment their power, their purses, or both.

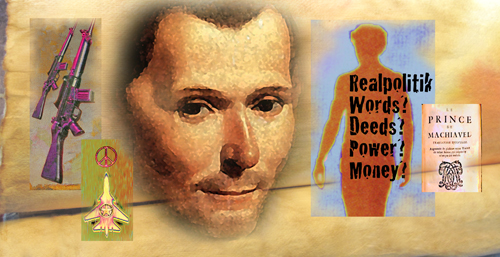

Niccolo Machiavelli and his legacy

The Genesis of Realpolitik

As you can appreciate, the gap between words and actions hasn’t narrowed that much in the last five centuries. But this stark discrepancy in politics between theory and practice impressed a brilliant Florentine diplomat named Niccolò Machiavelli (1469-1527) so much that he wrote The Prince, in which he gives advice to statesmen on the basis of a frank assessment of political realities rather than on pious fantasies.

Machiavelli had many experiences which inspired his insights. One such was meeting Cesare Borgia. For a time Machiavelli considered him Italy’s best hope for unification against the French and Spanish invaders. (It didn’t happen.) In 1503, Machiavelli met Borgia for a second time, in the course of a diplomatic mission. During the encounter he learned a thing or two about Borgia’s modus operandi. At one point, Borgia ran into problems with some noblemen of a nearby town run by the Orsini family, who weren’t too happy about Borgia’s plans for territorial expansion. The Orsinis were invited by Borgia to the city of Senigallia, allegedly to conduct peace talks and reach a reciprocally suitable agreement. As soon as they set foot inside the walls they were captured and executed. Diplomacy Italian style, circa 1500 CE.

Another illuminating episode took place in the Borgia-occupied city of Cesena, a territory that needed to be ‘pacified’. I’ll let Machiavelli tell the story: Cesare Borgia “appointed Remirro de Orco, a cruel, no-nonsense man, and gave him complete control. In a short while de Orco pacified and united the area… As soon as he found a pretext, he had de Orco beheaded and his corpse put on display one morning in the piazza in Cesena with a wooden block and a bloody knife beside. The ferocity of the spectacle left people both gratified and shocked” (The Prince). So Borgia first had one of his henchmen do his dirty work, knowing that this would anger the people; but since a prince needs popular support, he then found an excuse to execute the henchman, thus giving the people what they wanted and deflecting their ire.

No wonder Bertrand Russell called The Prince “a handbook for gangsters.” As Tim Parks aptly puts it in his Introduction to the Penguin translation, “Machiavelli’s little book was a constant threat. It reminded people that power is always up for grabs, always a question of what can be taken by force or treachery, and always, despite all protests to the contrary, the prime concern of any ruler.”

Machiavelli was the first modern writer to systematically think in terms of what is called realpolitik, or, ‘political realism’. Since then, political realism has seen a number of developments, and has gathered an impressive array of supporters. Arguably the most influential early philosopher in this vein was Thomas Hobbes, whose Leviathan, or The Matter, Forme and Power of a Commonwealth Ecclesiasticall and Civil (1651) articulated the need for a strong ruler in order to avoid the violent ‘state of nature’ to which, according to Hobbes, we would otherwise inevitably revert. This state he famously characterized as ‘a war of all against all’:

“In such condition there is no place for industry, because the fruit thereof is uncertain, and consequently no culture of the earth, no navigation nor the use of commodities that may be imported by sea, no commodious building, no instruments of moving and removing such things as require much force, no knowledge of the face of the earth, no account of time, no arts, no letters, no society, and which is worst of all, continual fear and danger of violent death, and the life of man, solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.”

Well, who wouldn’t give up a few liberties here and there in order to avoid that? Among the practitioners of Machiavellianism, as one might fairly label the approach, is a who’s who of early-modern and contemporary statesmen; from the French Cardinal Richelieu (of Three Musketeers fame), to the Prussian monarch Frederick the Great; from the Italian Camillo Benso of Cavour, to another Prussian, Otto von Bismarck; all the way down to Mao Zedong, Charles de Gaulle, and Henry Kissinger.

A Socratic Way

Yet there is another way of looking at the relationship between ethics and politics, without having to give in to the hypocrisy of Renaissance popes and modern politicians. It was put forth by Socrates in the fifth century BCE, and hinges on the wannabe statesman’s character.

Socrates was known as the annoying ‘gadfly’ of ancient Athens, always intent to show people that they really didn’t know what they were talking about when it came to crucial concepts such justice (as shown in Plato’s Republic) or piety (as in his Euthyphro). But another major aspect of Socrates’ activities emerges from less appreciated sources. For instance, Xenophon’s Memorabilia (c.370 BCE) gives two episodes in which Socrates makes it his business to advise about a political career – against or in favor of, depending on who he’s talking to.

On one occasion, Socrates meets up with a very young Glaucon, Plato’s elder brother. Glaucon is bent on a political career, and he thinks he knows what that entails. Socrates appears duly impressed, but as usual he begins questioning his interlocutor:

“‘Well, Glaucon, as you want to win honor, is it not obvious that you must benefit your city?’

‘Most certainly.’

‘Pray don’t be reticent, then; but tell us how you propose to begin your services to the state.’…

Glaucon remained dumb, apparently considering for the first time how to begin.” (Memorabilia, 3.6.3–4.)

At one point Glaucon tells Socrates that Athens will be able to raise its revenues by waging war. To this Socrates responds:

“‘In order to advise her whom to fight, it is necessary to know the strength of the city [of Athens] and of the enemy, so that, if the city be stronger, one may recommend her to go to war, but if weaker than the enemy, may persuade her to beware.’

‘You are right.’

‘First, then, tell us the naval and military strength of our city, and then that of her enemies.’

‘No, of course I can’t tell you out of my head.’” (3.6.8.)

Next Socrates asks whether Glaucon has a good estimate of how long the grain reserves will last, as those are crucial to feed the city. Glaucon’s response is that that task is too overwhelming, and he didn’t feel like carrying it out. Socrates at this point chides Glaucon, reminding him that if one wishes to take charge of a household, one must bother with exactly the sort of details that Glaucon has so far neglected when it comes to affairs of state. Glaucon replies:

“‘Well, I could do something for uncle’s household if only he would listen to me.’

‘What? You can’t persuade your uncle, and yet you suppose you will be able to persuade all the Athenians, including your uncle, to listen to you? Pray take care, Glaucon, that your daring ambition doesn’t lead to a fall! Don’t you see how risky it is to say or do what you don’t understand?’” (3.6.15–16)

That apparently did the trick, and Glaucon postponed his dream of becoming a statesman. In fact, he never became one. Instead, he fought valiantly at the battle of Megara, at the height of the Peloponnesian War with Sparta, in 424 BCE, the year after this conversation took place. He later became a competent musician, as Socrates attests in the Republic.

Contrast this episode with one that took place years later involving Charmides, Glaucon’s son:

“Seeing that Glaucon… was a respectable man and far more capable than the politicians of the day, [who] nevertheless shrank from speaking in the assembly and taking a part in politics, [Socrates] said:

‘Tell me, Charmides, what would you think of a man who was capable of gaining a victory in the great games and consequently of winning honor for himself and adding to his country’s fame in the Greek world, and yet refused to compete?’

‘I should think him a poltroon and a coward, of course.’” (3.7.1)

Soon Charmides realizes to his chagrin that Socrates is talking about him in relation to politics, and is setting up the usual Socratic trap: “Don’t refuse to face this duty then: strive more earnestly to pay heed to yourself; and don’t neglect public affairs, if you have the power to improve them” (3.7.9). In this particular case, however, things did not go well. Charmides did enter into politics, but had the misfortune to serve Athens under the Spartan-appointed Thirty Tyrants after Sparta’s defeat of Athens in the war.

Charmides died in the battle of Munichia in 403 BCE. This underscores a point appreciated many centuries later by Machiavelli: the statesman needs skill, but also luck. Cesare Borgia was very skilled, at least by Machiavelli’s standards, but in the end he ran out of luck. His strongest supporter, his father, Pope Alexander VI, died before the two of them could make enough progress in the pursuit of their projects.

Socrates, however, would have insisted on a third ingredient besides skill and luck: virtue. This insistence becomes very apparent in the course of the First Alcibiades (which is generally ascribed to Plato, despite some doubts about its authorship).

Alcibiades was a friend and student of Socrates, and very much wanted to be his lover – at least according to the speech he gives in Plato’s Symposium. At the time of the dialogue in the First Alcibiades, he was twenty years old, handsome, rich, charismatic, and full of self-confidence. Alcibiades wanted to make a difference in the world, so he went to Socrates for advice on how best to follow the path of virtue. But in the course of the conversation it becomes increasingly clear that Alcibiades is more interested in glory and self-aggrandizement. At one point Socrates diagnoses his problem in blunt terms: “Then alas, Alcibiades, what a condition you suffer from! I hesitate to name it, but, since we two are alone, it must be said. You are wedded to stupidity, best of men, of the most extreme sort, as the argument accuses you and you accuse yourself. So this is why you are leaping into the affairs of the city before you have been educated.” (Alcibiades I.26).

Naturally, Alcibiades does not listen to his mentor and follows his instincts instead. This results in one of the most astounding series of political disasters in all antiquity, including a major role in the Athenian defeat in the Peloponnesian War, and ending with Alcibiades’ death at the hand of Persian agents acting on behalf of Sparta. I tell the whole sordid tale as part of the bigger picture concerning ethics and politics in my new book, How To Be Good: What Socrates Can Teach Us About the Art of Living Well (Basic Books, 2022).

Cesare Borgia seizing power

Cicero’s Third Way

While Machiavelli argued that skill and luck, not virtue, make for a good leader, Socrates bet everything on virtue. The Roman advocate, statesman, and philosopher, Marcus Tullius Cicero would say they both only got part of the picture: a good leader needs not only a good character, but also needs to be able to pragmatically navigate complex situations through trade-offs and compromises. That is why Cicero was critical of his friend Cato the Younger, a stern and uncompromisingly virtuous Stoic who eventually did more damage than good to the Roman Republic: “As for our friend Cato, you do not love him more than I do: but after all, with the very best intentions and the most absolute honesty, he sometimes does harm to the Republic. He speaks and votes as though he were in the Republic of Plato, not in the scum of Romulus” (Letters to Atticus, 2.1.8). The fact is that we all live in ‘the scum of Romulus’ (Romulus was the legendary founder of Rome). Good leaders realize that their followers are flawed, and act accordingly – without going to the extremes of a Cesare Borgia.

Cicero knew what he was talking about, since he struggled his whole life to save the Roman Republic. He shifted his political allegiances and his short-term objectives in order to always keep his eyes on the ultimate prize. And he did this while trying to maintain his integrity of character and his philosophical commitments. In the end he failed to save the Republic, possibly because the Republic was no longer a sustainable model and had to give way to Empire as a matter of historical necessity; or perhaps because too many others around him behaved in a Machiavellian fashion, putting their own thirst for power and glory ahead of the common good. They could get away with such behavior because the Roman people had given up demanding that their leaders at least try to behave as virtuously as they talked.

Let us not make the same mistake.

© Massimo Pigliucci 2022

Massimo Pigliucci is the K.D. Irani Professor of Philosophy at the City College of New York. His books include How to Be a Stoic (Basic Books) and The Quest for Character (Basic Books). More by him at massimopigliucci.org.